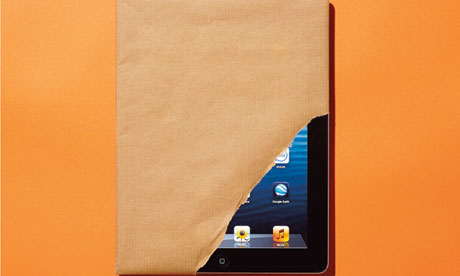

Emma Cook attempts to apply the principles of the 5:2 fasting to cut down her family's tech time

Could really work? check it out

Could really work? check it out

My eldest is feeling

the absence most. He is morose, restless, roaming from room to room like

a caged lion. Photograph: Aaron Tilley for the Guardian

Until recently, technology was taking over our family.

At first it was amusing, the sight of three kids bunched up on the sofa

– 10, nine and two – arms and legs entwined, in tablet heaven; Louis on

his mini iPad, Evie on her iTouch, Amelia on my iPad.

But the novelty quickly waned. The lack of interaction was spooky. No conversation, arguing or laughter. Instead, the perpetual soundtrack of shrieky American voices and inane CBeebies theme tunes. I wasn't exactly a great role model, enchanted by my new Mac Air and iPhone, checking my emails while they did their homework.

Then, along with half the country, I tried the Fast Diet – two days of abstinence made bearable with the promise of feasting the next day. Perfect for a generation hooked on instant gratification.

As the pounds began to fall, I turned to my zoned-out screen junkies and wondered if the same principle would work for them. Why not a 5:2 screen diet? A lukewarm rather than cold turkey, to cut down their usage rather than abstain altogether?

Actually, 5:2 isn't that lukewarm – it works out as almost 30% less food each week. In screen terms, that's a lot less CBeebies and Minecraft.

Dr Richard Graham, a child and adolescent psychiatrist who launched the first technology-addiction programme three years ago, was at first sceptical. He treated Britain's youngest iPad addict, a four-year-old obsessed with playing games for up to four hours a day. A real digital detox would be 72 hours in one block at least, he said, giving users time to adapt to those early feelings of agitation and craving. "You need to experience that difficult period and to create offline activities that feel different but pleasurable." But he agreed it could work, as long as I set firm boundaries during the 24 hours.

"It's about taking away, no compromise," he said. "And, hopefully, changing your behaviour for the rest of the time." Graham's three golden rules? Stay active, stay active, stay active. "This isn't about activity as distraction," he explained. "It's drawing on your body in a different way, using your physical self on those days off and noticing how different it feels. Getting out and about is a good start."

Day one of our family screen diet coincides with half-term. Twelve hours yawn ahead of us. There's only one way out. I book three tickets to The Great Gatsby. It means leaving the house and doing something we all enjoy, but it is also one huge screen. I call Graham to check I'm not cheating. "Fine," he says. "It's a different sensory experience and it's something you're sharing together. On the downside, it's had rather mixed reviews."

I leave Amelia at home with the nanny under strict instruction to hide all devices and stick to Where's Spot? "To make this watertight, there must be no weak links," Graham advises. No indulgent grandmas, partners or nannies. I'm the only weak link, I think, checking emails while the children aren't looking.

The film is a success, but back home, trouble flares by late afternoon. My eldest is feeling the absence most. He is morose, restless, roaming from room to room like a caged lion. Amelia finger-paints, Evie sculpts Fimo, but Louis can't let go. He forages through the kitchen drawer looking for a discarded mobile. I find him under a duvet upstairs on an old Nintendo game. I drag him downstairs to play chess. He reads, then chases his sister around the kitchen. Somehow this all takes only half an hour. It's 3.30pm.

We go to the park, play in the adventure playground, paddle in the pool – ekeing out those hours away from home, like alcoholics avoiding the pub.

Week two is all about pushing boundaries. Louis: "The internet is the future, this is just going backwards." Evie: "Surely Facetime counts as communication – it's only a phone call." Amelia, wistfully: "Where iPad?"

"No compromise," I bark at all of them, and creep to the kitchen to text my husband. I think it's going rather well.

That evening the two eldest children both help me put Amelia to bed when they'd normally be Facetiming friends. Our household is noisier, more argumentative, less passive and solipsistic. One month later, I'm increasing the fast principle to weekend afternoons. Best of all, Louis is now on board. I ask him to compare fast days with feast ones. "Er, it's the difference between sitting on the sofa with a screen and you shouting at us all, or sitting at the kitchen table, drinking tea and chatting to you."

"Thank God that long Amish nightmare is over," Phil, the father in Modern Family, says when their week-long screen diet ends. I thought I'd feel the same way, but I don't: this is just the beginning.

• Make sure everyone is on-message – no weak links.

• Encourage them to talk about how they feel during those two days off, so "they are learning to self-monitor and reflect about what's going on", Graham says.

• Create pleasurable offline experiences – physical activity is the best. The aim here, according to Graham, is to "build up resilience so you can balance on- and offline activities, and benefit from both.".

But the novelty quickly waned. The lack of interaction was spooky. No conversation, arguing or laughter. Instead, the perpetual soundtrack of shrieky American voices and inane CBeebies theme tunes. I wasn't exactly a great role model, enchanted by my new Mac Air and iPhone, checking my emails while they did their homework.

Then, along with half the country, I tried the Fast Diet – two days of abstinence made bearable with the promise of feasting the next day. Perfect for a generation hooked on instant gratification.

As the pounds began to fall, I turned to my zoned-out screen junkies and wondered if the same principle would work for them. Why not a 5:2 screen diet? A lukewarm rather than cold turkey, to cut down their usage rather than abstain altogether?

Actually, 5:2 isn't that lukewarm – it works out as almost 30% less food each week. In screen terms, that's a lot less CBeebies and Minecraft.

Dr Richard Graham, a child and adolescent psychiatrist who launched the first technology-addiction programme three years ago, was at first sceptical. He treated Britain's youngest iPad addict, a four-year-old obsessed with playing games for up to four hours a day. A real digital detox would be 72 hours in one block at least, he said, giving users time to adapt to those early feelings of agitation and craving. "You need to experience that difficult period and to create offline activities that feel different but pleasurable." But he agreed it could work, as long as I set firm boundaries during the 24 hours.

"It's about taking away, no compromise," he said. "And, hopefully, changing your behaviour for the rest of the time." Graham's three golden rules? Stay active, stay active, stay active. "This isn't about activity as distraction," he explained. "It's drawing on your body in a different way, using your physical self on those days off and noticing how different it feels. Getting out and about is a good start."

Day one of our family screen diet coincides with half-term. Twelve hours yawn ahead of us. There's only one way out. I book three tickets to The Great Gatsby. It means leaving the house and doing something we all enjoy, but it is also one huge screen. I call Graham to check I'm not cheating. "Fine," he says. "It's a different sensory experience and it's something you're sharing together. On the downside, it's had rather mixed reviews."

I leave Amelia at home with the nanny under strict instruction to hide all devices and stick to Where's Spot? "To make this watertight, there must be no weak links," Graham advises. No indulgent grandmas, partners or nannies. I'm the only weak link, I think, checking emails while the children aren't looking.

The film is a success, but back home, trouble flares by late afternoon. My eldest is feeling the absence most. He is morose, restless, roaming from room to room like a caged lion. Amelia finger-paints, Evie sculpts Fimo, but Louis can't let go. He forages through the kitchen drawer looking for a discarded mobile. I find him under a duvet upstairs on an old Nintendo game. I drag him downstairs to play chess. He reads, then chases his sister around the kitchen. Somehow this all takes only half an hour. It's 3.30pm.

We go to the park, play in the adventure playground, paddle in the pool – ekeing out those hours away from home, like alcoholics avoiding the pub.

Week two is all about pushing boundaries. Louis: "The internet is the future, this is just going backwards." Evie: "Surely Facetime counts as communication – it's only a phone call." Amelia, wistfully: "Where iPad?"

"No compromise," I bark at all of them, and creep to the kitchen to text my husband. I think it's going rather well.

That evening the two eldest children both help me put Amelia to bed when they'd normally be Facetiming friends. Our household is noisier, more argumentative, less passive and solipsistic. One month later, I'm increasing the fast principle to weekend afternoons. Best of all, Louis is now on board. I ask him to compare fast days with feast ones. "Er, it's the difference between sitting on the sofa with a screen and you shouting at us all, or sitting at the kitchen table, drinking tea and chatting to you."

"Thank God that long Amish nightmare is over," Phil, the father in Modern Family, says when their week-long screen diet ends. I thought I'd feel the same way, but I don't: this is just the beginning.

How to make it work

• Be black and white with your children during their two days offline. No screen time also means no Facetime and no checking texts. Be clear, and hide their devices if necessary. Don't compromise.• Make sure everyone is on-message – no weak links.

• Encourage them to talk about how they feel during those two days off, so "they are learning to self-monitor and reflect about what's going on", Graham says.

• Create pleasurable offline experiences – physical activity is the best. The aim here, according to Graham, is to "build up resilience so you can balance on- and offline activities, and benefit from both.".

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for your comment, keep reading our news and articles